zeljkovranjes/ark is a full-stack monolithic application with a robust Identity and Access Management (IAM) solution at its core. Initially developed as a closed-source component for a side project, I've since decided to release it to the public.

Below, I'll walk through my thought process and reasoning behind key design decisions during the development of this project. For each component, I'll detail the advantages, disadvantages, and potential alternative approaches.

Task System:

The Task System was designed to delegate database operations (it's pretty much just an actor). Rather than repeatedly reinstantiating database connections to update fields, we can queue desired tasks through a specialized system. This approach improves function clarity and execution efficiency.

Consider the difference between traditional database operations and the Task System approach:

Traditional approach:

pub fn create_permission(database: PostgresDatabase, permission: Permission) -> Result<T> {

/* perform operation here */

}

Task System approach:

pub fn create_permission(permission: Permission) -> TaskResult<T> {

/* queue message here */

}

Instead of direct instantiation through a CRUD function, the Task System handles the instantiation when it receives the task.

To successfully compose and send a task to the Task System, you need three components: TaskType identifies which handler to use, TaskHandler<D> assigns a specific "action" to Task<D, R, P> where D is Database, and Task<D, R, P> performs the actual task where D is Database, R is TaskRequest, and P is The Type.

Once these components are defined, you must register the TaskType with the corresponding listener. You can see how to register a listener here.

With registration complete, you can create a function that sends requests to the task channel:

pub fn create_role(role: Role) -> TaskResult<TaskStatus> {

let task_request = Self::create_role_request(role);

TaskManager::process_task(task_request)

}

fn create_role_request(role: Role) -> TaskRequest {

TaskRequest::compose_request(RoleCreateTask::from(role), TaskType::Role, "role_create")

}

TaskRequest composes a request that the Task System can interpret. Then, calling TaskManager::process_task(task_request) will return either a Completed or Failed status. If you expect a custom return type, you can use TaskManager::process_task_with_result::<T>(request) instead.

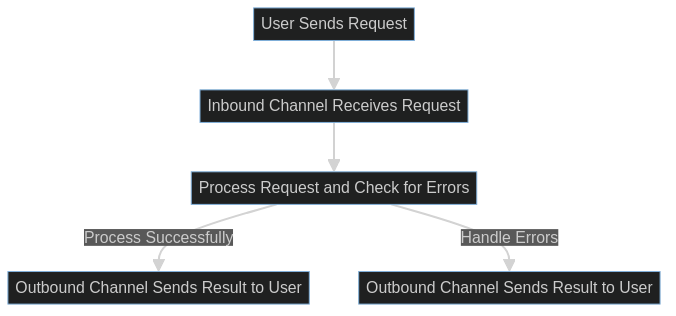

The Task System uses a bidirectional channel flow. When the system receives a request, it first routes to the INBOUND channel, then sends results to the OUTBOUND channel. This bidirectional setup allows reliable result retrieval.

Advantages include function simplicity and granular control. Disadvantages include major overhead and no support for nested tasks. Alternative approaches could use a message broker instead of channels, implement Redis pub/sub instead of channels, add tasks to a hashmap first then have the task system pull directly from the hashmap (though this would require multiple hashmaps for each type, adding overhead), or use serialization to reduce reliance on generic types.

Cache System:

The Cache System follows a similar pattern to the Task System but uses Redis instead of PostgreSQL. I separated these systems because of a limitation: you cannot call a task within another task (or a channel within a channel) unless it comes from a different instance. The Cache System uses a separate channel instance, allowing cache operations to be called from within tasks.

IAM (Identity And Access Management):

The IAM implementation in this project is relatively straightforward. It doesn't include more advanced features like effects, resources, or policies, focusing instead on user roles and permissions.

Permission System:

I designed the permission system for flexibility. Permissions are stored in PostgreSQL but cached differently than other data. Rather than using the Cache System to store them in Redis, they're cached locally in a HashMap. This approach was chosen based on scale considerations: while you might expect hundreds of permissions, you could have hundreds of thousands of users.

The permission caching mechanism is straightforward but distinct from the main Cache System. If you want to use a local cache, you can bypass the Cache System and use LocalizedCache<T>, where T represents the type you want to cache (e.g., Permission). You would then implement LocalizedCache<Permission> for your PermissionCache type.

When calling fn add(item: T), the system adds three keys: permission_id, permission_name, and permission_key. I chose to add these three keys because each field is unique in the database, allowing permissions to be retrieved by ID, name, or key.

All key values use an Arc<T> (where T is the same as in LocalizedCache<T>), creating a shared state. This means when you implement an fn update() and modify a field, it automatically updates the other two references.

The schema includes permission_id (UUID of the permission randomly generated using the uuid crate), permission_name (Name of the permission like "Ban User"), and permission_key (Key of the permission like "admin.ban.user"). The permission_name and permission_key can follow any format, though the examples above represent the ideal structure.

Roles and permissions are interconnected. To maintain consistency, the role type includes a field pub role_permissions: Vec<String>, which contains only the IDs of associated permissions. This approach was chosen because the permission ID is the only immutable field within a permission.

Role System:

I think of roles as collections of grouped permissions. This allows for predefined permission sets that can be assigned to specific roles, eliminating the need to assign individual permissions (like "ban") to each user. Instead, users can be assigned a role with pre-configured permissions, ensuring consistency across the application.

The schema includes role_id (UUID of the role randomly generated using the uuid crate) and role_name (Name of the role like "Moderator"). The role_name and role_id can follow any format, though the examples represent the ideal naming convention.

User Management:

Examining the schema.sql file and the iam_users table, you'll notice the absence of password fields. This is by design, as users authenticate exclusively through OAuth2 providers such as Google and Discord.

The iam_users table includes security_token and security_stamp fields, inspired by ASP.NET Core's security model. When the security_stamp changes, the security_token is automatically invalidated.

The security_stamp doesn't have a specific model but uses the String type. To generate a valid stamp, the function fn generate_security_stamp(security_stamp: String, action: &str) is used. This function captures the current time in milliseconds, hashes it with SHA-256, and converts it to a hexadecimal string.

The model for security_token is:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Serialize, Deserialize)]

// security token for the user...

pub struct SecurityToken {

pub token: String,

pub expiry: u128,

pub action: String,

}

The token generation process calls SecurityToken::new(security_stamp: String, action: &str), serializes the model with serde_json and converts to hexadecimal, then stores the hexadecimal representation in the database.

To retrieve the token, call decode_then_deserialize(security_token: Option<String>), which decodes the hexadecimal string, deserializes it to the SecurityToken type, and returns None if the token is empty.

To generate a token with a specific action, use UserSecurity::create(action). For example, to create an email reset token:

UserSecurity::create("email_reset");

Then, in your route handler for /auth/email_reset, check if the SecurityToken exists and verify that the action is set to "email_reset". If not, deny access.

This completes the technical overview of the current state of the Ark project. I welcome feedback and contributions to further improve its architecture and functionality.